By John Harms

Since the pandemic came to live with us, we’ve seen three AFL games at the MCG – via the television. And while the canned crowd noise becomes second nature, and there is footy to enjoy, it’s obviously not the same.

The world has changed. Footy has changed.

As a kid I was footy-nuts. But it wasn’t until my twenties that I started to reflect on it all. Why did I love footy so much? Why did it mean so much to me? What was it all about?

I discovered that I wasn’t the first to ask these questions. And I found essays and articles by Serious Writers and Thinkers which were about footy. Brian Matthews. Manning Clark. Don Watson. Geoffrey Blainey. Martin Flanagan.

And the poets. I discovered Colin Thiele’s ‘Oval Barracker’ and Peter Goldsworthy’s ‘Trick Knee’, Philip Hodgins ‘Country Football and ‘The Drop Kick’, and Peter Kocan’s ‘The Champion’. Of course I laughed and smiled and nodded when I read ‘Life Cycle’ by Bruce Dawe. Subsequently, when teaching high school English, I used some of these footy poems.

One theme that emerges in some of this writing is the role of the crowd collectively, and of individual people in the crowd whether you describe them as barrackers, fans, spectators or what. The people play the game.

We act. We are the players. The footballers facilitate it. They make it possible for us to act.

Mark O’Connor was probably writing about the lights at the MCG when he penned ‘Under Martian Eyes’. He observes:

The players, swathed in their overcoats

push the incompetent celebrants on with voice.

By this thesis, I have played many a game of football at the MCG. Actively yelling. Bouncing around. Applauding freely. Shaking my fist at the umps. As have the thousands around me.

My happiness is at stake and if I have to wear my lucky Max Rooke badge to ensure a Geelong victory then I should wear it. No, I will wear it.

Being at the footy is one of the many things we are missing at the moment. And the sheer fun of being part of it with our fellow footy-lovers. Bruce Dawe appreciated this.

People relate so strongly to Bruce Dawe’s poetry because it is about us. It is about ordinary, everyday, garden-variety Australian life. So simple. So obvious. So profound. I had studied him myself at school in the 1970s and continued to return to those poems and his new poems as they were collected in anthologies such as Condolences of the Seasons and Sometimes Gladness.

I could mention so many of his poems. Two which really spoke to me are ‘Homo Suburbiensis’ about the Australian home and yard, and ‘The High Mark’ which is about the symbolism of the speccie.

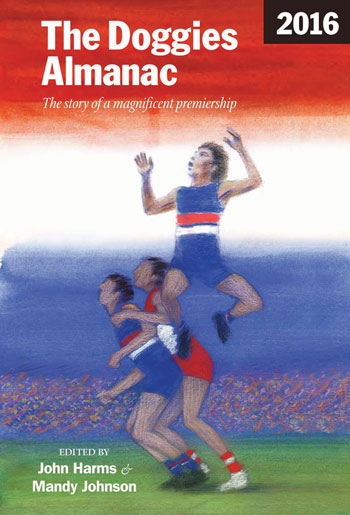

I didn’t know Bruce well, although we met and corresponded a few times, but I felt I knew him from his poetry. When the Western Bulldogs won the 2016 premiership and Liam Picken was a star, Jim Pavlidis painted an image of the famous final-quarter mark which became the cover of The Doggies Almanac 2016. I wrote to Bruce to ask if we could use his poem ‘The High Mark’ as a foreword to the book. A Doggies sympathiser, he said that would give him much joy. So we did.

He sent me a hand-written Christmas greeting later that year, a card with these words:

September Song

May more Septembers come to bring

More pennants to your team,

Until that too-long interval

Seems but a distant dream

- But then, as all true lovers know,

There’s nothing half as sweet,

When expectations are fulfilled,

There’s dancing in the street!

Happy New Year to you and all Doggy Fans!

Bruce Dawe and Family

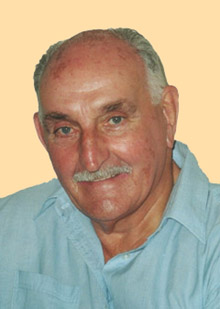

Bruce Dawe died on April 1 this year, having turned 90 in February. He spent much of his life in Queensland.

He, of all people, would understand how we are missing football, and the life we once knew. He, of all people, would understand (and recommend) the hope that life’s richness will return, or that we will find a new richness.

Vale Bruce Dawe. The People’s Poet. Who wrote about The People’s Game.

Read Bruce Dawe’s poems which are referred to in this piece at the Footy Almanac website.

John Harms is a writer and publisher. He is editor-at-large of the Footy Almanac.

Since the pandemic came to live with us, we’ve seen three AFL games at the MCG – via the television. And while the canned crowd noise becomes second nature, and there is footy to enjoy, it’s obviously not the same.

The world has changed. Footy has changed.

As a kid I was footy-nuts. But it wasn’t until my twenties that I started to reflect on it all. Why did I love footy so much? Why did it mean so much to me? What was it all about?

I discovered that I wasn’t the first to ask these questions. And I found essays and articles by Serious Writers and Thinkers which were about footy. Brian Matthews. Manning Clark. Don Watson. Geoffrey Blainey. Martin Flanagan.

And the poets. I discovered Colin Thiele’s ‘Oval Barracker’ and Peter Goldsworthy’s ‘Trick Knee’, Philip Hodgins ‘Country Football and ‘The Drop Kick’, and Peter Kocan’s ‘The Champion’. Of course I laughed and smiled and nodded when I read ‘Life Cycle’ by Bruce Dawe. Subsequently, when teaching high school English, I used some of these footy poems.

One theme that emerges in some of this writing is the role of the crowd collectively, and of individual people in the crowd whether you describe them as barrackers, fans, spectators or what. The people play the game.

We act. We are the players. The footballers facilitate it. They make it possible for us to act.

Mark O’Connor was probably writing about the lights at the MCG when he penned ‘Under Martian Eyes’. He observes:

The players, swathed in their overcoats

push the incompetent celebrants on with voice.

By this thesis, I have played many a game of football at the MCG. Actively yelling. Bouncing around. Applauding freely. Shaking my fist at the umps. As have the thousands around me.

My happiness is at stake and if I have to wear my lucky Max Rooke badge to ensure a Geelong victory then I should wear it. No, I will wear it.

Being at the footy is one of the many things we are missing at the moment. And the sheer fun of being part of it with our fellow footy-lovers. Bruce Dawe appreciated this.

People relate so strongly to Bruce Dawe’s poetry because it is about us. It is about ordinary, everyday, garden-variety Australian life. So simple. So obvious. So profound. I had studied him myself at school in the 1970s and continued to return to those poems and his new poems as they were collected in anthologies such as Condolences of the Seasons and Sometimes Gladness.

I could mention so many of his poems. Two which really spoke to me are ‘Homo Suburbiensis’ about the Australian home and yard, and ‘The High Mark’ which is about the symbolism of the speccie.

I didn’t know Bruce well, although we met and corresponded a few times, but I felt I knew him from his poetry. When the Western Bulldogs won the 2016 premiership and Liam Picken was a star, Jim Pavlidis painted an image of the famous final-quarter mark which became the cover of The Doggies Almanac 2016. I wrote to Bruce to ask if we could use his poem ‘The High Mark’ as a foreword to the book. A Doggies sympathiser, he said that would give him much joy. So we did.

He sent me a hand-written Christmas greeting later that year, a card with these words:

September Song

May more Septembers come to bring

More pennants to your team,

Until that too-long interval

Seems but a distant dream

- But then, as all true lovers know,

There’s nothing half as sweet,

When expectations are fulfilled,

There’s dancing in the street!

Happy New Year to you and all Doggy Fans!

Bruce Dawe and Family

Bruce Dawe died on April 1 this year, having turned 90 in February. He spent much of his life in Queensland.

He, of all people, would understand how we are missing football, and the life we once knew. He, of all people, would understand (and recommend) the hope that life’s richness will return, or that we will find a new richness.

Vale Bruce Dawe. The People’s Poet. Who wrote about The People’s Game.

Read Bruce Dawe’s poems which are referred to in this piece at the Footy Almanac website.

John Harms is a writer and publisher. He is editor-at-large of the Footy Almanac.