Join us in the Cricketers’ Suites this AFL Season

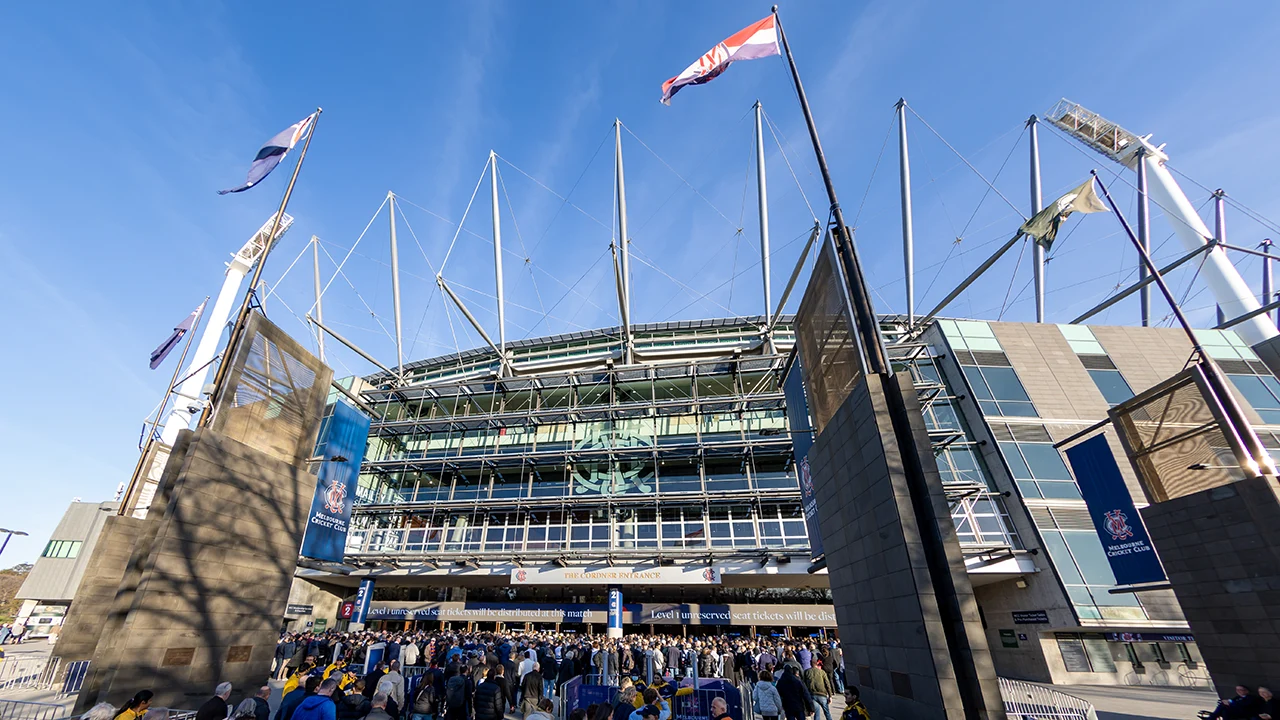

The Club is pleased to offer members the opportunity to entertain guests in the Cricketers’ Suite for a hospitality experience during the 2026 AFL Premiership Season.

View the Melbourne Cricket Club's Annual Reports.